Co-editors: Seán Mac Mathúna • John Heathcote

Consulting editor: Themistocles Hoetis

Field Correspondent: Allen Hougland

Rudolf

Kasztner

Ten

Questions to the Zionists from Rabbi

Weissmandel THE

KASTNER TRIAL - shown at the Jewish Film Festival in

1997 Shamash:

The

Jewish Internet Consortium: Holocaust Home

Page Rudolf Vrba, born Walter

Rosenberg in Tropoljany, Czechoslvakia in 1924, was the

Jewish Slovak resistance fighter who escaped from Auschwitz

in 1944 to get the news of the Holocaust to the world. He

contacted the Jewish Council and told them what was going on

in the death camp and the fate with awaited the Hungarian

Jews. His account also reached Rudolf Kastner who ignored

it. Vrba later commented: Rudolf Vrba, born in

Czechoslovakia in 1924 Some historians have argued

that a giving the Hungarian Jews this warning would have

made no differance - because they claimed the Jews of

Hungary were not prepared to revolt and that any rebellion

against the Nazi's would have been suicidal. Vrba, though,

sees it differantly: Rudolf Vrba

shown holding a Hebrew version of his Book "I

Escaped Auschwitz" during a recent visit to Israel.

He presently lives in Canada. Read an account of

this published in The

Jerusalam Post Below is a full account of

Vrba's dramatic escape from Auschwitz on Friday, April 7th

1944 - just hours before the first night of Passover. The

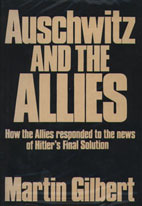

extract is from Auschwitz

and the Allies by

Martin Gilbert (Michael Joseph, London,

England,1981) On April 7 (1944) two trains

reached Auschwitz from western Europe. The first, from

Holland, contained 240 Jews, of whom sixty-two men and

thirty-eight women were tattooed and sent to the barracks,

and the remaining 140, including twenty-two children, were

gassed. Later that same day a second train arrived from

Belgium, and 206 men and a hundred women were tattooed and

sent to the barracks, while the rest, 319 in all, including

fifty-four children, were sent straight to the gas

chamber. The destruction of the family

camp on March 7 had made a profound impression on a young

Slovak Jew, Walter Rosenberg, who subsequently changed his

name to Rudolf Vrba. Several of Vrba's close friends had

perished in the family camp, and he felt an urgent need to

inform the outside world both of what had already happened

at Auschwitz, and of the preparations which those in the

camp knew to be taking place to kill a substantially

increased number of victims, most probably from Hungary. "I

was attracted,' Vrba later wrote, 'by the possibility to

damage the plans of the Nazis by divulging them to the

Hungarian Jewish population while they are still in freedom,

and can take to the streets.' (1) Vrba had been in Auschwitz

since June 1942, and for nearly two years he had found ample

opportunity to observe the killing process at work. On three

previous occasions he had made plans to escape, in December

1942, May 1943 and January 1944, but had been unable to

carry them out. Now, together with a fellow Slovak, Alfred

Wetzler, he contacted the secret International Resistance

Group inside the camp, and put his plan of escape to David

Szmulewski one of the representatives of the resistance

leaders 'I have been told,' Vrba later wrote, 'that due to

my inexperience, personal volatility (impulsiveness) and

other factors the leadership dismissed my intentions as

unreliable." (2) The resistance leaders

understood, however, Vrba's intense personal feelings about

the destruction of the family camp, and gave him their

assurance that, even if they could not help him escape, no

obstacle would be put in his way. On March 31 his resistance

contact, Szmulewski saw him again, to tell him of the

resistance leaders' decision. "Szmulewski himself,' Vrba

later recalled 'was very sorry because of the unfavourable

"higher decision" but expressed the hope that in the case of

"no success" I would be able to avoid interrogation and thus

avoid a catastrophe for those who had had contact with me

before.' The two escapees were

determined to alert the outside world to the reality of

Auschwitz, and to the fate that seemed to be in store for

the Jews of Hungary. Wetzler, who was twenty-six, had been

an actual witness of the destruction of the Theresienstadt

family camp. Vrba was nineteen and a half. Both had been

born in Slovakia. Both had been brought to Auschwitz nearly

two years before. What these two men had seen and learned

during those two years was to provide the basis for the

first comprehensive report to reach the west. From August 1942 to June 1943

Vrba had worked in a special 'Clearing Commando', known

colloquially as 'Canada', then situated in Auschwitz Main

Camp. On the arrival of each train at the railway sidings,

the Commando's task was to drag out the dead bodies, and

then take all the luggage of the deportees for sorting, and

to prepare it for dispatch to Germany. Thus for ten months

Vrba was present at the arrival of almost most every train,

and committed to memory their place of origin and the number

of deportees in each. In June 1943 Vrba was

transferred from 'Canada' to become one of the registrars in

the Quarantine Camp at Birkenau, and as a registrar he had

the opportunity of speaking to those new arrivals who had

been selected from the incoming trains for slave labour,

instead of for gassing. Here again, he both knew and

memorized the details of the incoming transports, including

the sequence of tattoo numbers allocated to each group as it

arrived. In addition, many of the trucks taking people from

the railway sidings to Crematorium IV drove past within only

a few yards of Vrba's 'office'. As Vrba himself later wrote:

From his 'office', Vrba also

witnessed the construction of a new railway siding inside

Birkenau itself. Work on this siding, or 'ramp had begun on

15 January 1944. 'The purpose of this ramp,' Vrba later

recalled, "was no secret in Birkenau the SS were talking

about 'Hungarian Salami' and 'a million units' . . . my

lavatory was 30 yards from the new ramp, my office about 100

yards." Vrba had also been able to make

contact with the Czech family camp, as his work as registrar

enabled him to move during the daytime between several

sections of Birkenau He could make full use of this ability,

he later recalled, 'by taking a bundle of papers' with him,

moving to a section of Birkenau adjacent to the family camp.

Then he could contrive to 'get lost' among the prisoners in

that section, and without even having to shout, he could

speak across the barbed wire between the sections, to other

prisoners. There were even times when he had been able to

pass written messages across to the family camp, and to

receive messages in reply. Two days before the actual

gassing of the family camp, the SS had imposed an internal

camp curfew. But a number of those marked out to die had at

the same time been transferred to the very section in which

Vrba was then a registrar. 'Thus, for the last two days of

their lives , he later recalled, 'I had unlimited contact

with them." (4) Like Vrba, Alfred Wetzler had

also been a registrar, but in different parts of Birkenau,

including the mortuary. He too had established contacts

which enabled him to collect information about every aspect

of the killing process. The facts which he and Vrba were

able to assemble and to memorize, included the number of

Jews 'put to death by gas at Birkenau from April 1942 to

April 1944, listed by their country of origin, and the

dimensions of the camp. While planning their escape,

Vrba and Wetzler had even been able to make contact with

several of the Jews forced by the SS to drag the corpses

from the gas chambers to the crematorium. These Jewish slave

labourers were formed into a special unit, or

Sonderkommando. At regular intervals, they too would

be gassed, and then replaced by a new group. But those whom

Vrba and Wetzler contacted were able to give them details

about the size and workings of the gas chambers themselves.

These facts also the two men committed to memory. Two hours before the evening

roll-call of April 7 Vrba and Wetzler were hidden by their

colleagues in a specially prepared hide-out which a number

of inmates had prepared during work on an extension of the

camp which was then under construction beyond the camp's

inner perimeter. This area, known as 'Mexico', was being

prepared to house the expected Hungarian Jews. The hide-out was a gap in a

woodpile, made up of wooden boards. These boards were being

stored as part of the building material for the extension of

the camp. Before the inmates returned to their barracks

within the inner perimeter, they sprinkled the surrounding

area with petrol soaks and tobacco, to prevent the two

hundred guard dogs of Birkenau, kept there for just such

occasions, from sniffing out the would-be escapees. This

latter advice had come from the experience of Soviet

prisoners-of-war. At evening roll-call, after the

'Mexico' workers had returned to their barracks, the sirens

sounded. Two prisoners were missing. The guards and dogs

began their search. For three days and nights there was a

high security alarm, with continuous roll-calls and

searches. (5) Throughout those three days a tight cordon of

SS guards was kept around both the inner and outer

perimeters. But the hide-away remained

undiscovered, and by the evening of April 10, the camp

authorities assumed that the two men had already got away.

The cordon of SS guards which had surrounded the outer

perimeter of the camp withdrawn. On April 9 the head of the SS

units responsible for guarding the camp, Waffen SS Major

Hartenstein had already telegraphed news of the escape to

Gestapo headquarters in Berlin. Copies of his telegram were

sent to the SS administrative headquarters at Sachsenhausen

to all commanders of Gestapo and SID units in the east, to

all Criminal Police units, and to all frontier police posts.

The telegram gave the names of the two men, Identified them

as Jews, and added: 'Immediate search unsuccessful. Request

from you further search and in case of capture full report

to concentration camp Auschwitz". (6) The telegram went on to state

that Himmler himself had been informed of the escape, and

that the fault 'of any guard' had not so far been

determined. The search within the outer

perimeter of the camp having been called off at 10 p.m. on

April 10, Vrba and Wetzler slipped past the outer line of

watchtowers, and with incredible courage set off southwards

toward Slovakia. After their escape, Vrba and

Wetzler had worked their way southwards from Birkenau

'without documents, without a compass, without a map, and

without a weapon". (7) Carefully avoiding the German 'new

settlers' who lived, as at Kozy, in former Polish homes, who

were often armed, and had the authority to shoot

"unidentifiable loiterers' at sight, they headed steadily

towards the mountains, shunning all roads and paths, and

marching only at night. One evening they were fired on by a

German police patrol, but managed to escape into the forest.

Later they met a Polish partisan, who guided them towards

the frontier, and then, on the morning of Friday April 21,

they crossed into Slovakia, finding refuge with a farmer on

the Slovak side, in the small village of Skalite. On April 6, the day before Vrba

and Wetzler began their escape, Reuven Zaslani of the Jewish

Agency had already warned British intelligence in Cairo of a

German radio broadcast in which the Germans 'propose

eliminating a million Jews in Hungary'. (8) On the following day, as Vrba

and Wetzler crouched in their woodpile, and were hiding

within half a mile of Crematorium IV, the Geneva Zionists

were once again telling the Allied representatives in

Switzerland what they knew of the fate of European Jewry

This time they told their story to the United States

Minister in Berne, Leland Harrison, and his first Counsellor

of Legation, J. Klahr Huddle. Once more Gerhart Riegner and

Richard Lichtheim who headed the delegation, reported for

more than an hour on the news which had reached them from

Nazi Europe. Several thousand Dutch Jews, they said, had

beer) saved from deportation as a result of receiving

Palestine certificates. But the Polish Jews interned in

Vittel were less fortunate: recently the Government of

Paraguay 'had refused to recognise" those documents and

passports which had been issued by the Paraguayan consul in

Berne, while several other South American consuls who had

issued similar documents 'had been dismissed'. The Zionists and the American

diplomats then had what was described as ,a general

discussion' about the 'tragic fate' of the Jews of Europe.

Riegner handed Harrison two photographs. One showed "the

dead bodies of the Jews in Transnistra", Rumanian Jews who

had been deported eastward in the autumn of 1941, and the

other showed what Riegner called 'one of the death chambers

in Treblinka". This second photograph, Riegner

told Harrison, 'was corroborating evidence to the report

lately issued by Polish circles and describing the death

camp of Treblinka". (9) Once again, there was no

mention of Auschwitz. Not even its name appeared in the

report of this long meeting. Yet the gas chambers there had

already been in operation for nearly two years. And as Vrba,

Wetzler, and their terrible information began the journey

southward, the SS were making plans to build two more gas

chambers, to repair the crematoria, and to begin what they

hoped would be the rapid, uninterrupted, and secret

destruction of the 750,000 Hungarian Jews whose fate they

now controlled. From Pages

201-205 Throughout April (1944), while

the SS prepared to deport the Jews of Hungary, other Jews

were being brought to Auschwitz as before. On April 9 the

first of three trains reached Auschwitz from the Majdanek

concentration camp, which was evacuated as the Red Army

drove steadily westwards. For eight days these "evacuees"

had been shunted towards Auschwitz in a sealed train,

without water, or medical help. During the journey, twenty

of them cut their way out of the train at a wayside station,

and tried to escape. All were shot. A further ninety-nine

were found dead on arrival at Auschwitz. Tile survivors were

tattooed, and sent to the barracks. On the following day, April 10,

a train reached Auschwitz from Italy, and on April 11 from

Athens. Of 1,500 deportees in this second train, 1,067 were

gassed. On April 29 a further train arrived from Paris,

including the Vittel deportees with their once precious, now

valueless Latin American passports. On April 30, from a

train from Italy, only thirteen men were sent to the

barracks, while all the women, children and old people were

gassed. Equally unknown to the Allies,

the Jews of Hungary were being prepared for deportation to

Auschwitz. The first stage of the Nazi plan, the scaling of

the Jews into ghettoes, had already begun on April 16, in

Ruthenia. Nine days later, the question of rescue took an

unexpected, dramatic turn : oil April 25, Joel Brand, a

leading Hungarian Zionist, was taken to SS headquarters in

Budapest. As Brand recalled two months later, Eichmann

'snapped' at him, as soon as lie was seated: Brand then recalled the

following conversation: Eichmann:

Quite. Well, I want goods for blood. Brand: I

did not understand at first and thought Eichmann meant

money. Eichmann:

No. Goods for blood. Money comes second. Brand: What

goods? Eichmann:

Go to your international authorities, they will know. For

example - lorries. I could imagine one lorry for a

hundred Jews, but that is only a suggested figure. Where

will you go ? Brand: I

must think . . . (11) This meeting between Brand and

Eichmann, unknown at the time either to the Jewish Agency or

to the Allies, was to lead within a few weeks to both the

Agency and the Allies becoming directly involved in the fate

of Hungarian Jewry, and in an SS act of deception on a

massive scale: for Eichmann wanted Brand to make contact

with the Jewish Agency representatives in Istanbul, and with

the Allies, and to offer a commercial barter, the Jews of

Hungary, alive, in exchange for goods and money: 'Goods for

blood', as Eichmann had expressed it. With the truth about Auschwitz

still unknown in the west, such an offer contained a

tantalizing appeal. But at the very moment when it was being

made, evidence was reaching the Jewish leadership in

Slovakia which contained full and horrific details of the

gassings at Auschwitz. The source of this news was the two

Auschwitz escapees, Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler, whose

message had begun its westward journey with their escape

from Auschwitz 'on April 10 and their meeting with the

Slovak farmer at Skalite on April 21. As Vrba later

recalled: The farmer's name was Canecky.

During lunch he explained to Vrba and Wetzler that 'in

almost all the neighbouring villages' there were Jewish

doctors who had been exempt from deportation in the summer

of 1942 because of the 'dire lack' of doctors in Slovakia.

The exemption had covered the doctor's wife and children,

but not his parents, brothers or sisters. The farmer then told the

escapees that in the town of Cadca there was one such Jewish

doctor, a Dr. Pollak. Vrba realized that this was the same

man whom he himself had met at the time of his own

deportation in June 1942, and who, as a doctor, had been

deleted at the last moment from the deportation

list. To walk over the mountains to

Cadca would have taken the two men at least three days. But

if they could wait in Skalite until Monday morning, they

could take a train. This they did, dressed as local

peasants, and pretending to transport the farmer's pigs for

sale in Cadca's Monday market. As the local train was

controlled by local Slovak gendarmes, and not by Germans,

the risk for someone speaking Slovak, and dressed as a

peasant, was relatively small. So it was that the two men

reached Cadca without incident. There, as Vrba later

recalled: When Dr. Pollak learned

from me that all his 'resettled' relatives were dead, he

became somewhat shaky, and asked me what he could do for

me. I asked him to immediately contact the Jewish Council

in Bratislava. Before I left his office he, Dr. Pollak,

suggested that lie put bandages on my feet so that the

nurse would not suspect something unusual, because I was

a long time in his office (about fifteen

minutes). He gave me the address of

some of his friends, and we, i.e. Wetzler and myself,

slept in Cadca We travelled to Zilina next morning by

train, dressed as peasants. Oil the morning of Tuesday,

April 25, at about to a.m. we met the first

representative of the Jewish Council, Mr. Erwin Steiner,

in a park in Zilina. We (Wetzler and l) were drinking

slivovitz in the park and waiting for Steiner. Without

hair, in peasant shirts and drinking slivovitz in public

we attracted no attention, as this was a common habit of

newly recruited (already shorn) soldiers in Slovakia.

Thus we met the Jewish Council, with my feet still in

bandages provided by Dr. Pollak.' (12) On hearing the two escapees'

story, Steiner at once contacted the Jewish community in

Bratislava, the Slovak capital. The man to whom he spoke, by

telephone, in Bratislava was Oskar Krasnansky a chemical

engineer, and a leading Slovak Zionist. Although Jews were

not normally allowed to travel by train, Krasnansky managed

to obtain permission from the Police, and made his way to

Zilina. At Steiner's house Krasnansky

found the two escapees: 'They were in poor health, and

undernourished', he later recalled. 'They had eaten almost

no food for three weeks'. Krasnansky was impressed by the

escapees' 'wonderful memory', and for two days he

cross-examined them on the 'reality' of Auschwitz. Then,

after providing them with false Aryan papers, he sent them

for safety to the town of Lipovsky Mikulas. (13) Using Council documents brought

specially from Bratislava, Krasnansky checked the escapees'

account of the arrival of trains from Slovakia to Auschwitz

with the Council's own statistics of the departure of these

trains from Slovakia to their previously 'unknown

destination'. Then Krasnansky wrote a covering note to their

report, stating that it contained 'only what one or other,

or both, experienced, witnessed, or had knowledge of

directly'. Krasnansky added: Hence the statements are

to be considered as completely authentic.

(14) The question was now discussed

in Bratislava: what was to be done with this Vrba-Wetzler

report? According to Krasnansky, he himself wrote it out in

German, and gave it to a typist, Gisi Farkas, who made

several copies. 'One copy', he later recalled, 'we sent to

Istanbul. But it never arrived there. The man to whom we

gave it, who was making the journey, had been sent from

Istanbul as a "reliable courier". But possibly he was a paid

spy. As far as we later learned, he gave it to the Gestapo

in Budapest'. Krasnansky handed a second copy

of the report to the Slovak Orthodox rabbi, Dov Weissmandel

who had contacts with the Orthodox community in Switzerland,

and who offered to try to smuggle it there, for transmission

to the West. (14) A third copy was given to

Monsignor Giuseppe Burzio the Papal Chargé d'Affaires

in Bratislava, who went it on to the Vatican on May 22,

after himself questioning the two escapees. But the

Vatican's own records suggest that Burzio's report only

reached there five months later.' (15) The most urgent need, Vrba and

Wetzler believed, was to transmit the report to Hungary, and

to alert Hungarian Jewry to their own potential fate.

Krasnansky himself translated the Vrba-Wetzler report into

Hungarian, and prepared to give it to Rudolf

Kasztner the head

of the Hungarian Jewish rescue committee, on his next visit

to Bratislava. Kasztner who made the short

train journey from Budapest fairly frequently, was expected

in Bratislava before the end of April. But on April 25, the

very day on which Krasnansky was cross-examining Vrba and

Wetzler in Zilina, Kasztner and the Hungarian Jewish

leadership in Budapest were receiving Eichmann's offer to

negotiate 'goods for blood': to avoid the death camps

altogether in return for a substantial payment. On that fatal day, April 25,

two events had coincided: the truth about Auschwitz had

reached those who had the ability to make it known to the

potential victims, and the offer had been made to negotiate

'goods for blood'. Those Hungarian Jewish leaders who wished

to follow up the negotiations Were unwilling to risk the

negotiations by publicizing the facts about the annihilation

process at Auschwitz. Yet that process was known to them

from April 28, three days after Eichmann's first meeting

with Brand, when Kasztner travelled to Bratislava, where he

was given a copy of the Vrba-Wetzler report, and took it

back to Budapest. (16) But by then Kasztner and his

colleagues in the Zionist leadership in Hungary were already

committed to their negotiations with Eichmann, and to the

dispatch of their colleague, Joel Brand, to Istanbul. They

therefore gave no publicity whatsoever to the facts about

Auschwitz which were now in their possession. To this day, Vrba remains

convinced that had the facts which he and Wetzler brought to

Bratislava been immediately publicized and circulated

throughout Hungary, many of the 450,000 Jews who were later

to be deported, but who were as yet still in Hungary, would

have been stirred to resist, evade or otherwise obstruct

their deportation. Had the deportees had "knowledge of hot

ovens", Vrba later wrote, 'Instead of parcels of cold food,

they would have been less ready to board the trains and the

whole action of deportation would have been slowed

down". Not urgent warnings to their

fellow Jews to resist deportation, but secret negotiations

with the SS aimed at averting deportation altogether, had

become the avenue of hope chosen by the Hungarian Zionist

leaders. Their people thus became the innocent victims of

one of the countless Nazi deceptions of the war; "a clever

ruse", as Vrba himself later reflected, 'to neutralize the

potential resistance of a million people', and lie added:

During the first two weeks of

May the deportations to Auschwitz continued from Paris, from

Yugoslavia, from Berlin, and from the industrial labour camp

at Blechhammer. On May 14 a train arrived bringing sick and

old Jews, and Jewish children, from Plaszow, a slave labour

camp in the suburbs of Cracow. All were gassed. For the Jewish Agency, the

dispatch of Palestine certificates continued, their sole

known means of rescue. During May the first certificates

began to reach Belgium, sent from the Palestine Office in

Geneva through the International Red Cross, and these gave

protection, it was later discovered 'to some 600

recipients'. (18) Among the many enquiries that

had been made was one oil behalf of Yitzhak Gruenbaum

(Greenbaum), Polish-born chairman of the Rescue Committee of

the Jewish Agency, whose son Eliezer had been living in

Warsaw on the outbreak of war. Early that spring Gruenbaum

himself had telegraphed to Gerhart Riegner in Geneva: 'Find

my son'. Riegner's first reaction, as he later recalled, was

amazement that Gruenbaum should even imagine that it was any

longer possible to find anybody in Poland: But Riegner did not shrug off

the request. Instead, tic later recalled: This was indeed so; on March 1

a postcard from Eliezer Gruenbaum reached the World Congress

in Geneva, confirming receipt of the parcel. From Geneva,

Richard Lichtman at once wrote to Jerusalem to inform

Eliezer's father that his son was alive, and that the

postcard had come from a camp in Upper Silesia. The name of

the camp was Jawischowitz. It was, Lichtheim added,

'practically the same place as Birkenau'. (20) Jawischowitz was in fact one of

several industrial regions in the Auschwitz area to which

Jewish slave labour from Auschwitz and Birkenau were sent.

It was in no way 'practically the same place'. But the name

'Birkenau' like that of 'Auschwitz' still masked its true

function from those who used it. According to Eliezer

Gruenbaum's postcard, which had been sent from Jawischowitz

on April 29, he had received 'three food parcels' through

the World Jewish Congress relief organization, Relico, and

it was Relico's Geneva office which had received his

postcard, which had taken only six days to make its journey

from Upper Silesia to Switzerland. The name 'Birkenau' again

appeared in a Jewish Agency message on May 3. although once

again, as in Lichtheim's letter of May 1, it was not linked

or associated in any way with the name 'Auschwitz', of which

it was so integral a part. The second mention of Birkenau

was in a telegram from Yitzhak Gruenbaum's representative in

Istanbul, Eliezer Leder who reported to Jerusalem that the

British Consulate in Istanbul had confirmed the Palestine

certificates recently issued for Hungary and Rumania, and

that he, Leder, now wished to know whether it was 'advisable

sending same Birkenau'. (21) This telegram is a clear

pointer of just how little was known of the

Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. But ignorance and hope were a

powerful combination; and hope that at least some Jews could

be rescued was given further encouragement on May 5, when

the British Consul in Geneva, H. B. Livingston, informed the

Jewish Agency representatives there that the Germans had

agreed to a third exchange, 'covering 279 Jews for 111

Germans', and that this exchange could take place 'about

mid-May'. (22) Here was a possibility of

saving a further 279 Jews from Nazi Europe; Jews from Poland

who, if they could be found, could now be brought out. Both

the relatives of Palestinian Jews, and 'veteran Zionists'

were eligible. The problem was to find them. In the previous

exchange, a majority of those on the list had never been

found. They had, in fact. already been deported, and gassed.

Now the search began again. 1 Rudolf Vrba, letter to Martin

Gilbert, 30th July 1980. 2 Rudolf Vrba, letter to Martin

Gilbert, 11th July 1980. 3 Deposition by Dr. Vrba for

submission at the trial of Adolf Eichmann. Israeli Embassy,

London, England, 16th July 1961. Vrba papers. 4 Rudolf Vrba, letter to Martin

Gilbert, 30th July 1980. 5 The horror of roll-calls at

Auschwitz has been described by many survivors - such as

Filip Witter, Auschwitz Inferno London, England,

1979, pages 1-6. On 28 October 1940, for example, 84 Poles

died during a single morning's roll-call in Auschwitz Main

Camp (report sent by the Polish Underground on 31 October

1942, received in London on 28th May 1943, Polish Institute

and Sikorski Museum archive. PRM 76/1/13). 6 Text of the telegram in Erich

Kulka. Five Escapes from Auschwitz, Yuri Suhl

(editor), They Fought Back: The Story of Jewish

Resistance in Nazi Europe, London 1968, page

232. 7 Rudolf Vrba, letter to the

Martin Gilbert, 29th November 1980 . 8 Report of an interview,

Foreign Office papers, 921/152, 6(5) 44/14, Top Secret.

Zasani's purpose, the interviewer recorded, was to advance

further the Jewish Agency's scheme 'for infiltrating Jews

into Hungary and Rumania to stimulate resistance among the

Jews there'. 9 "Note: re visit to American

Legation, Berne on Friday 7 April 1944", Geneva, 11th April

1944, copy in Central Zionist Archives, L 22/92. 10 Left blank in the original

text of the interrogation. 11 Interrogation report, File

No. SIME/P 7769, No. SIMET 7769, page 18 18. in Foreign

Office papers, 371/4-,81 1. The interrogating officer was

Lieutenant W. B. Savigny. 12 Rudolf Vrba, letter to

Martin Gilbert, 30th July 1980. 13 Quoted in Erich Kulka,

Five Escapes from Auschwitz, Yuri Suhl (editor),

They Fought Back: The Story of Jewish Resistance in Nazi

Europe, London 1968, page 233. Krasnansky's note was

first published by the War Refugee Board in Washington on 26

November 1944. Al part of the official publication of the

Vrba-Wetzler report. 14 Oskar Krasnansky,

conversation with Martin Gilbert, Tel Aviv, Israel, 22

December 1980. 15 Report No. 2144 (A.E.S. S

7679/44), sent from Bratislava 22 May 1944, annotated in the

Vatican, 22 and 26 October 1944. Bruzio's covering note of

22 May 1944 is reprinted in full in Actes et Documents du

Saint Siège Relatifs à la Seconde Guerre

Mondiale, volume 10. Le Saint Siège et les

Victimes de la Guerre, January 1944 -July 1945. Vatican

1980. 16 Statement by Oskar

Krasnansky and Dr. Neumann, Yad Vashem archives. 17 Rudolf Vrba, letter to

Martin Gilbert, 30th July 1980. 18 Rescue Committee of the

Jewish Agency for Palestine, Bulletin, 'Jerusalem,

January 1945, page 7. 19 Gerhart Riegner, letter to

Martin Gilbert, 1 October 1980. 20 Central Zionist Archives,

L22/135. Eliezer Gruenbaum survived the war, and emigrated

to Palestine, but was later killed during the first

Arab-Israeli war of of 1948. 21 Central Zionist Archives, S

26/1190. 22 Central Zionist Archives L

22/56. © Martin Gilbert, 1981.

"It is my

contention that a small group of informed people, by

their silence, deprived others of the possibility or

privalage of making their own decisions in the face of

mortal danger"

"Passive and

active resistance by a million people would create panic

and havoc in Hungary. Panic in Hungary would have been

better than panic which came to the victims in front of

burning pits in Birkenau. Eichmann knew it; that is why

he smoked cigars with the Kasztners', "negotiated",

exempted the "real great rabbis", and meanwhile without

panic among the deportees, planned to "resettle" hundreds

of thousands in orderly fashion . .

."

". . . it was part

of my duty to make a summarized report of the whole

registration office, which report was daily conveyed to

the so-called Political Department of the concentration

camp Auschwitz. Having this duty enabled me again and

again to obtain first hand information about each

transport which arrived in the area of the Auschwitz

concentration camp." (3)

You know who l am.

I solved the Jewish question in Slovakia. I have

stretched out my feelers to See If your international

Jewry is still capable of doing anything. I will make a

deal with you. We are in the fifth year of the war. We

need . . . (10) and we are not immodest. I am prepared to

sell you all the Jews. I am also prepared to have them

all annihilated. It is as you wish. It is as you wish.

Anyway, what do you on want ? I presume for you the most

important are the men and women who can produce

children.

Brand:

I am not the man to decide that old men and women should

be left behind, and only people capable of producing

children should be saved.

'We met

accidentally on the march within one kilometre of the

German-Slovak border. He was working in his fields. He

saw that we had crossed the border "on our stomachs", and

invited us for lunch.'

I walked into Dr.

Pollak's surgery pretending to be a patient. There was a

female nurse present in his office, so I pretended I came

to complain about a 'gentleman's disease' and I said I

wanted the woman nurse to go out. Once alone with Dr.

Pollak I explained to him briefly who I was and from

where I knew him and from where I now came.

The statements

coincide with the reports, undoubtedly only fragmentary,

but reliable, that have been received up until now, and

the information supplied on individual transports

corresponds exactly with the official

listings.

Passive and

active resistance by a million people would create panic

and havoc in Hungary. Panic in Hungary would have been

better than panic which came to the victims in front of

burning pits in Birkenau. Eichmann knew it; that is why

he smoked cigars with the Kasztners', "negotiated",

exempted the "real great rabbis", and meanwhile without

panic among the deportees, planned to "resettle" hundreds

of thousands in orderly fashion . . . (17)

If anybody knew

what the fate of Polish Jewry had been, it is Gruenbaum.

He was the personification of the fight for Jewish rights

in Poland before the war. It was a completely crazy idea

to find an individual there, to find the son of a father

in Poland. after two and a half years of killing . .

.

I had a crazy idea

of my own. I sent tell Red Cross packages to ten

different camps, each in the name of Yitzhak Gruenbaum's

son. And from one camp, confirmation came . . .

(19)

References