Co-editors: Seán Mac Mathúna • John Heathcote

Consulting editor: Themistocles Hoetis

Field Correspondent: Allen Hougland

|

COINTELPRO: FBI Activities in Hollywood Cointelpro Revisited - Spying & Disruption Armies of Repression: The FBI, COINTELPRO and Far Right Vigilante Networks |

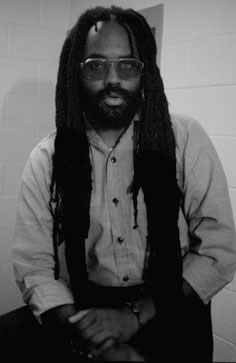

Photograph by Tom Filmyer Wesley Cook grew up in a poor housing project in black North Philadelphia. His sister Lydia remembers those days: "My mother had six children, and Mumia was one of twins. He was a jolly, happy child. As he got older, he loved to read. He used to go out and sit on the steps and read to the other children in the neighbourhood. When he was old enough, he would visit neighbourhood churches, seeking answers to questions. He did well in school. He loved to write. We used to call him a little nerd because he was in his own world reading his books and exploring the world around him." His high school Swahili teacher gave him the name Mumia, which he kept, and Cook took his last name meaning "Father of Jamal" after the birth of his first son. Now 41, he is married and, according to his sister, "has many children. He would just adopt them. He was a loving father - you could always find one of his children with him." Serving as Minister of Information for the Philadelphia branch of the Black Panther Party for most of his teen years, Jamal got serious journalistic training. In his later days as a journalist, Jamal became known as "the voice of the voiceless" on account of his willingness to publicise the views and actions of minorities and the poor. His commentaries, highly critical of the American government and police, have been published in over 40 newspapers in the United States and abroad, in addition to American periodicals such as The Nation and the Yale Law Journal. Throughout the 1970's, he worked full-time at radio stations in Philadelphia, and broadcast his reports across nationwide networks, including National Public Radio. Just 11 months before his arrest, Philadelphia magazine crowned Mumia Abu-Jamal "one of the people to watch in 1981". In a way the editors of Philadelphia never would have predicted, they were right. Racially divided Philadelphia reacted to Officer Faulkner's killing along polarised lines. Whites charged Jamal was receiving favourable treatment from fellow journalists in their news reports of the incident, and they evoked the memory of their decorated and admired brother in uniform, Officer Daniel Faulkner. Blacks claimed Jamal was the victim of a system that routinely brutalises people of colour, and they praised his journalistic talents and gentle soul. An atmosphere of anger and mistrust prevailed six months after the shooting as Jamal was brought to trial before Philadelphia Common Pleas Judge Albert Sabo. Known locally as "the hanging judge," Sabo has handed down more death sentences than any other judge in America - and all but two of them to non-whites. Conflict between Sabo and Jamal arose almost immediately. Unable to afford a lawyer and distrustful of court-appointed attorneys, Jamal chose to forego counsel and represent himself. On the third day of jury selection, prosecutors claimed Jamal was intimidating potential jurors and asked the court to bar him from self-representation. Sabo agreed. He appointed public defender Anthony Jackson to lead Jamal's defense. Jamal protested - loudly. The judge had him removed from the courtroom. This is where Jamal was to spend over half his trial, for he steadfastly refused to give up what he considered his constitutional right to represent himself. He attempted to exercise that right, through actions like addressing the court or cross-examining witnesses, whenever Sabo allowed him back into the courtroom - whereupon the judge would once again have him removed. Prosecutor Joseph McGill recounts the scenario he presented to the jury: "Jamal was the consummate coward. With a highly powerful weapon, he runs up and shoots Officer Faulkner in the back. The officer, only because of his training, is able to turn around and shoot Jamal in the chest, but falls down because of the momentum. What a coward. This is the hero of so many people. But that wasn't bad enough. What he then does is stand over the officer and unload the weapon. Most of the shots did not hit the body, but one did, and that was the one that went right between the eyes. Plenty of opportunity then to take his brother and go away, but he didn't do it - he continued to unload his gun. Certainly viewed by some to be an assassination, by others to be a planned move; most of that couldn't be proven." McGill produced four witnesses who claimed to have been at or near the murder scene. Cynthia White, a prostitute with an extensive criminal record, identified Jamal as Faulkner's killer. Two others testified that while they had not seen Jamal shoot the officer, they had heard shots shortly after they had seen Jamal run up to his brother and the policeman. And the fourth told the court that a black man had shot the policeman and had then sat down on the curb at the spot where police found the bleeding Jamal. Bolstering the state's case, Officer Gary Bell (the dead man's partner) and a security guard from Jefferson Hospital both testified that Jamal had arrogantly confessed to the murder ("I shot the motherfucker and I hope he dies") as he was wheeled into the emergency room. After seven days of testimony, the prosecution rested. The disorganised, fragmented, and underfinanced defense did little to attack the prosecution's case. Defense counsel Anthony Jackson, acting without his client's cooperation and (by his own admission) largely unprepared, did little more than call character witnesses to testify to Jamal's gentle nature. He was unable even to produce William Cook, who had been charged with assault on Officer Faulkner but subsequently disappeared, to testify on his brother's behalf. Nor did Jamal himself testify at the trial. In fact, he has never publicly told his own account of what happened that early December morning in 1981. ("I felt that to participate in a railroad would be to sanction that railroad.") In his statement to the jury during the penalty phase of the trial, Jamal twice told the panel "I am not guilty of these charges," a claim he maintains to this day. But in the end, the jury convicted Mumia Abu-Jamal of first-degree murder on July 2, 1982. The next day, Joseph McGill argued for the death penalty, reminding the jury that Jamal had been a Black Panther - and suggesting to them that he had been waiting for the opportunity to kill a cop. The twelve-person team, composed of ten whites and two blacks, voted to impose on Jamal the ultimate penalty: death by electrocution. Comments McGill: "The jury decided that the aggravating circumstances of killing a police officer in the line of duty outweighed the mitigating circumstances of no criminal record." Jamal fared no better in his appeal to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, which denied him all relief in 1989. A year later, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to even hear his final appeal. With all appeals failed, Jamal looked for new legal counsel. In 1991, he found it in defense attorney Leonard Weinglass, renowned trial counsel in such cases as the Chicago Seven and the Pentagon Papers, who has never lost a capital case. Weinglass's team, perhaps the first competent legal representation Jamal has ever received, have uncovered ample new evidence suggesting Jamal was wrongly convicted. For example, Jamal's gun: Weinglass explains that the prosecution "never was able to relate that gun to the actual shooting. Their expert said that the only bullet removed from the officer was too damaged to be tested to relate it directly to the gun." If anything, the ballistics evidence seems to exonerate Jamal: Weinglass discovered the report (unseen at the trial) of the medical examiner who had performed the autopsy on Daniel Faulkner, stating that the bullet removed from the policeman's back was a .44 caliber - while Jamal's gun had been a .38. The police admitted they had found no fingerprints on the gun, and claimed they had never tested it to see if it had recently been fired. "Officers handled that gun within five minutes," says Weinglass, "and within two hours it was in the police laboratory. They take the incredible position that no one bothered to smell the gun to see if it had been recently fired, nor to do neutron activation analysis on Mumia's hands to test them for traces of gunpowder. That's not believable." As for Jamal's hospital confession to the murder, Weinglass found that neither Faulkner's partner, Gary Bell, nor the security guard who testified to having heard it made any mention of it in their reports of that morning. In fact, Bell did not report such a confession for almost three months. Arresting officer Gary Wakshul, however, who was with Jamal the entire time from the murder scene to the operating room, wrote in his report of that same day that "the male Negro made no statement." Wakshul could not be produced at Jamal's trial; the police informed the court that he was "on vacation," and Judge Sabo refused the defense a continuance until his return. Weinglass's team have also discovered police reports documenting that four eyewitnesses told police the morning of the murder that they had seen a black man with dreadlocks - but not the bleeding Jamal - fleeing the murder scene. In court, only one witness stood by his initial statement about the man fleeing - Dessie Hightower, an elderly black man whom the jury apparently chose not to believe. One of the four could not be found by the defense to call to testify. The other two, cab driver Robert Chobert and prostitute Veronica Jones - both facing pending criminal charges at the time - denied in court having seen anyone flee. But Chobert has since revealed that he had received a prosecution's promise to reinstate his suspended drivers' license if he would retract his claim that he saw the shooter run away. And Jones has given Weinglass a sworn statement that police had offered her immunity from arrests if she would finger Jamal as the shooter, and "frightened me into changing my testimony so as not to help the defense" when she was later arrested on felony charges. She describes in her statement what she claims she saw the morning of the murder: "I was standing on the northwest corner of 12th and Locust streets when I heard three shots. I looked down Locust Street in the direction of the shooting. I saw a policeman down on the ground and two black men first walk and then sort of jog away from where he was lying on the ground. I also observed another black man standing near the Patco speedline entrance on the southeast corner of Locust and 13th streets." Many legal scholars now insist Jamal did not receive a fair trial, arguing that Judge Sabo abused his discretion and committed numerous constitutional errors, in violation of Jamal's constitutional rights. But last summer, just as Weinglass's team were uncovering the evidence that might help exonerate their client, Pennsylvania governor Tom Ridge signed Mumia Abu-Jamal's death warrant on June 2 and scheduled his execution for ten o'clock on the night of August 17 1997. His case rocketed to international attention. Street protests demanding a new trial for Jamal erupted in New York, Paris, Berlin, and other world capitals. "There's a sense of shock in Europe," says Julia Wright, journalist and daughter of author Richard Wright and lifelong resident of France. Wright recently joined a French delegation in delivering petitions demanding a new trial for Jamal - and bearing over sixty thousand signatures - to the press secretary of Governor Ridge in Harrisburg. "Mumia's book in France has become a best-seller in two months. A recent U.S. state department report stated that if Mumia were executed, there would be riots for about three days in Germany, Denmark, and France." Presidents Jacques Chirac of France and Nelson Mandela of South Africa, Foreign Ministers Kinkel of Germany and Derijcke of Belgium, and members of the Japanese Diet have urged the U.S. to grant Jamal a new trial, as have prominent intellectuals and celebrities around the world. British TV's Channel 4 ran a new half-hour program suggesting Jamal was wrongly convicted. Fixed in the lens of the media microscope, Judge Sabo granted him an indefinite stay of execution (pending further appeals) just ten days before Jamal was to be put to death. The following month, Jamal's petition for post-conviction relief , in which Leonard Weinglass described 19 constitutional errors committed in Jamal's trial and sentencing, was heard by none other than Judge Sabo, who in July had refused a defense petition that he recuse himself from the case. One error Weinglass described was the court's allowing the jury to include a man who had told the judge he could not be impartial, another man whose close friend was a policeman who had been shot in the line of duty, and the wife of a policeman - while excluding all but two African-American jurors. Another constitutional error Weinglass outlined hearing was the separation from his own trial that had been imposed on Jamal by his removal from the courtroom: "When a judge removes a person who faces a criminal charge," says Weinglass, "he has an obligation to see to it that that person can follow the proceedings, either by supplying transcripts or piping in the sound from the courtroom, so that the defendant retains contact with his own case. In Mumia's case, the judge denied transcripts, refused any kind of technical hook-up. When Mumia was out of court, he was out of contact with his case - and he faced the death penalty." Weinglass argues that any one of these errors warrants granting Jamal a new trial. "If we do get a new trial, Mumia will have for the first time - with the full protections that he didn't have in the first proceeding - the chance to tell his story." Weinglass says he would put Jamal on the stand at a new trial - unless the prosecution's case had already crumbled by that time. But such hopes were thwarted by Judge Sabo, who in autumn 1996, denied Jamal's petition for a new trial. According to Stuart Taylor in American Lawyer, the judge "flaunted his bias, oozing partiality toward the prosecution." Along the way, Sabo found Weinglass in contempt of court and fined him one thousand dollars; the judge also found co-counsel Rachel Wolkenstein in contempt for trying to correct the record, and had her jailed. The defense did, nevertheless, take advantage of the hearing to introduce into the record some of their new information about the morning of Officer Faulkner's shooting. They also benefited from original defense attorney Anthony Jackson's admitting on the stand that he had been woefully unprepared to handle Jamal's case. In addition, Debbie Kordansky - an eyewitness whom the defense had not been able to locate to call to testify at the trial - appeared in court for the first time. According to Weinglass: "She said that she told the police that morning that she had observed the scene from right after the shooting stopped and that she had seen someone running. She has that individual running on the same side of the street and in the same direction as the other three witnesses who also described someone running. So either four people who didn't know each other were hallucinating about the same event, or someone did actually run from the scene." Another witness called by the defense last summer bolstered the defense's "fleeing gunman" theory. As Weinglass tells it: "An individual came forward to testify and said he was arrested following the shooting because on the officer's body they had found his driver's license or application. They treated him as a suspect in the murder, as if he was the one who ran away. But throughout the trial they took the position that no one ran away." The witness who did not show up last summer, however, dealing the defense a major disappointment, was Jamal's brother and the main eyewitness to Daniel Faulkner's shooting, William Cook. Weinglass struggles to explain why Cook has never come forward: "No one - including his brother - thought Mumia would be convicted. But nine years later when Mumia lost his appeal, his brother realised Mumia might be executed. By then he was in no condition: he was living on the streets, homeless, he had become an addict, and he was frightened. He felt that if he came forward, he would be killed. We found him last summer, and he said he would testify, and he told us what happened: that he saw the shooting, that Mumia did not shoot the officer but was shot by the officer. We subpoenaed him, but when we were about to call him, his lawyer was informed by the court that if he were to testify for Mumia, he would be re-arrested on two outstanding charges. We asked the judge not to put over his head the threat of jail. The judge rejected that, and the brother made the decision not to come forward." Some have wondered whether William Cook shot Daniel Faulkner. But Leonard Weinglass says that "to my knowledge, there is no evidence" that anyone ever said they saw Jamal's brother shoot the officer. And Jamal's sister, Lydia Wallace, maintains that "Bill is more than willing to testify - at a new trial." In February 1996, Leonard Weinglass filed with the Pennsylvania Supreme Court an amended petition for a new trial for Jamal before a judge other than Sabo. He had expected a ruling by the end of 1996, but back then, he was not optimistic: "We're before a court that already sentenced Mumia to death in 1989. What they would have to admit in 1996 is that perhaps an error was made. And it's very hard to get a court to admit that once they have sentenced someone to death." Weinglass outlines his legal plans for Jamal's case: "If we lose in the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, we then have the opportunity to go into the Federal court in Philadelphia with a habeas corpus petition. We can relitigate before Federal judges - who are not elected and sit for life - the issues of the violations of constitutional principles. Forty percent of all state death penalty convictions are reversed by Federal judges. "This year, however, the Anti-Terrorism Act of 1995 became law. That bill greatly restricts our chances of winning in Federal court. It completely alters the 200 year history of habeas corpus in the United States. And it allows the execution of an individual who has been unconstitutionally convicted. And so we are very concerned. "If we lose in federal court, the final decision whether Mumia lives or dies is made by one person, who has no guidelines, no standards - it's just a flat-out, unquestioned decision - that person is Governor Ridge of Pennsylvania. He's a former prosecutor from a rural area of Pennsylvania who served as a combat leader in Vietnam. He's already signed Mumia's death warrant once, and when we got the stay of execution, he publicly said that he will sign another one if he gets the opportunity." Despite his penal status, Jamal remains an eloquent interpreter both of America's capital punishment system and of its racial problems. In his book Live from Death Row, he focuses on the racial discrimination that many judges and legal scholars say is inherent in America's imposition of the death penalty. Included in the book are his commentaries recorded in 1994 for National Public Radio but pulled from the NPR schedule after the Fraternal Order of Police protested their broadcast. The Philadelphia Police Department tried unsuccessfully to halt this book's publication. In 1995, the international group Human Rights Watch awarded Jamal a Lillian Hellman and Dashiell Hammett Grant, intended to assist writers who find themselves in financial need as a result of political persecution. Leonard Weinglass comments on the effect of notoriety on Jamal's case: "Mumia has achieved fame through his writing and his media attention. He has some high-profile supporters. And that unquestionably serves him well. But it doesn't give him an open road. Of all the people on death row, Mumia is the only one to have been targeted by a funded campaign to see to it that he is executed - namely, the Fraternal Order of Police. That's why this case is going to bring into collision the two contesting forces in the country on the issue of the death penalty and on the issue of the criminal justice system." Even Jamal's opponents are not surprised by the attention he has received. Prosecutor Joseph McGill remarks that "there's a highly financed organisation behind Jamal that is using him to put flesh and blood on the anti-death penalty position of many. He's attractive because he has some measure of talent in writing. He is certainly a champion of the oppressed. He has probably one of the best voices I've ever heard. He's just made for radio. And he's very firm and committed in his beliefs." On January 13, 1995, Mumia Abu-Jamal was moved to Pennsylvania's new super-maximum security or "control unit" prison, the State Correctional Institution at Waynesburg, Greene County. Nestled in rural hills just fifteen miles from the West Virginia border, its low earth-toned block walls blend into the grassy clearing where it furtively crouches, surrounded by multiple layers of green metal fences ringed with double-edged razor wire. Seeing no prisoners on the way, my cameraman and I are led by a genial female administrator through stark bright corridors, passing through a series of sliding metal security doors, to a cubicle where we will spend ninety minutes with Mumia Abu-Jamal. The official sits (as stipulated in prison regulations) just outside the little cinderblock room, and the door remains open during the interview. We walk in and find Jamal already seated there, wearing a blue cotton shirt and steel handcuffs, long dreadlocks hanging down. His deep voice echoes as it filters through narrow strips of screen at the ends of the thick Plexiglas barrier that separates him from us. A guard brings our wireless microphone around and pins it on Jamal's shirt. Jamal, who appears healthy and relaxed - happy to have a conversation, if not actual physical contact - is eager to begin talking. © Allen Hougland, 1997 |

|

|

|