Co-editors: Seán Mac Mathúna • John Heathcote

Consulting editor: Themistocles Hoetis

Field Correspondent: Allen Hougland

"There is no hope. Whether we

intellectuals are traitors or whether we are victims, in any

case we'd better recognize the utter hopelessness of our

situation. Why fool ourselves ? We're done for ! We're

licked !"

A

suicide wave among the world's most distinguished

minds would shock the peoples out of the lethargy,

would make them realize the extreme gravity of the

ordeal man has bought upon himself by his folly and

selfishness - Klaus Mann's last

essay

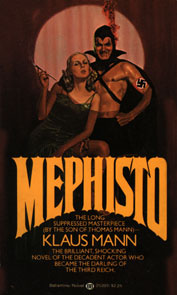

First

written in 1936, this scathing portrait of the Third

Reich was written by Klaus Mann whilst in exile from

his native Germany. When the novel was first published

in West Germany in the late 1950s, it became the

subject of the longest lawsuit in the history of

German publishing - dragging on for more than a decade

before the Supreme Court finally banned

publication.

The books subject

matter is based on his brother-in-law Gustaf

Grúndgren, who married his sister, Erika.

Grúndgren, who had once been a flamboyant

defender of communism, had a magnificent career in

Nazi Germany under the auspices of Herman Goring,

where he had been the leader of theatrical life in the

Third Reich. Mann wrote Mephisto to "analyse the

abject type of treacherous intellectual who

prostitutes his talent for the sake of some tawdry

fame and transitory wealth". The the lawsuit against

the book was brought by Gründgrens adopted

son.

The book has also

been published in France, Yugoslavia, Austria and

Switzerland

Klaus Mann came from a famous

family of German writers. He was a novelist, essayist, and

playwright whose works include Alexander (1929), Pathetic

Symphony (1936), and the autobiographical Turning Point

(1942). His father, Thomas Mann (1875-1955), has been

described as one of the "outstanding German literary figures

of the 20th century". One of Thomas Mann's brothers was

Heinrich Mann (1871-1950), who wrote novels of sharp social

criticism such as Professor Unrat (1905; tr. The Blue Angel)

and the trilogy The Poor (1917), The Patrioteer (1921), and

The Chief (1925).

Thomas Mann's novels developed

themes relating inner problems to changing European cultural

values. His first novel, Buddenbrooks (1901), brought him

fame. Translations of his shorter fiction, collected in

Stories of Three Decades (1936), including Tonio Kröger

(1903) and the classic Death in Venice (1912), reflect

Mann's preoccupation with the proximity of creative art to

neurosis, with the affinity of genius and disease, and with

the problem of artistic values in bourgeois society. These

themes are featured in his major work, The Magic Mountain

(1924). His tetralogy Joseph and His Brothers (1933-43) is a

brilliant study of psychological and mythological elements

in the biblical story. Later works include Doctor Faustus

(1947), The Holy Sinner (1951), and Confessions of Felix

Krull (1954). Translations of Mann's major political

writings denouncing fascism are published in Order of the

Day (1942); his major literary essays are collected in

Essays of Three Decades (1947). He left Nazi Germany in 1933

and lived in the U.S. after 1938, moving to Switzerland in

1953. He received the Nobel Prize in literature in 1929. His

daughter (Klaus's sister) Erika Mann (1905-69) was an

actress and author and was married to the poet W. H.

Auden.

The last

person to see him alive in 1949 (at Gulf Juan, French

Riviera), was the publisher and writer Themistocles Hoetis,

then editor of the famous literary magazine, Zero. He

had asked him to review of a book by Jean Coteau called

Letter to America for Zero. The day after Klaus handed the

finished manuscript to Themistocles, he committed suicide.

Shortly before, in June 1949, he had hinted at taking his

own life in his essay Europe's

Search for a New Credo.

He saw how the end of the war against fascism in Europe was

leading to a possible war with the Soviet Union - always

seen as the enemy of the West. He noted how "the ominous preparations

for war continue" and the "fatal rift between two world

powers" (the USSR and the USA) is "deepening from day to

day". Indeed, in April 1949 had seen the USA create it's own

military organisation to dominate Western Europe -

NATO

- fifty years old this year. The creation of NATO would lead

to the USSR forming it's own defensive military bloc - the

Warsaw Pakt - thus sowing the seeds for the division of

post-war Europe.

Klaus writes how a "a weak,

dissonant chorus, the voices of the European intellectuals

accompany the prodigious drama". He says that he has "heard

many voices on my travels, some aggressive and arrogant,

others gentle or flippant, passionate or sentimental. I have

yet to hear the harmony of coordinated sounds, the concert

of reconciled or peacefully competing forces". He meets a

young student of philosophy and literature in the university

town of Uppsala, Sweden. He says that this is what the

student tells him, but in a way, you think that he's also

talking himself:

Klaus observes

how:

"the struggle

between two great anti-spiritual powers - American money

and Russian fanaticism - does not leave any room in the

world for intellectual integrity or independence. We are

compelled to take sides and, by doing so, to betray

everything we should defend and cherish.

Koestler

is wrong when

asserting that one side is a little better than the other

- not quite black, just gray. In reality, neither side is

good enough - which is to say that both are bad, both are

black".

Thus he suggests a new

movement ("the movement of despair, the rebellion of the

hopeless ones"), should be launched by European

intellectuals:

"Instead of trying

to appease the powers that be, instead of vindicating the

machinations of greedy bankers or the outrages of

tyrannical bureaucrats, we ought to go on record with our

protest, with an unequivocal expression of our

bitterness, our horror. Things have reached a point where

only the most dramatic, most radical gesture has a chance

to be noticed, to awake the conscience of the blinded

hypnotized masses. I'd like to see hundreds, thousands of

intellectuals follow the examples of Virginia Woolf,

Ernst Toller, Stefan Zweig, Jan Masaryk. A suicide wave

among the world's most distinguished minds would shock

the peoples out of the lethargy, would make them realize

the extreme gravity of the ordeal man has bought upon

himself by his folly and selfishness".

The essay ends with the

student speaking in a trembling voice:

"Let's sign

ourselves to absolute despondency. It's the only sincere

attitude, and the only one that can be of any

help".

Clearly, there were no takers

for this suggestion of a "suicide wave" among Europe's

intellectuals, except sadly, that of Klaus Mann himself who

killed himself not long afterwards. Today, notably in

Germany, he is being recognised at last as - like his father

- as one of Europe's greatest literary figures.

©FLAME 1999